Solving the Cahn-Hilliard equation on complex geometries

The Cahn-Hilliard equation

The Cahn–Hilliard equation describes the process of phase separation, by which the two components of a binary fluid spontaneously separate and form domains pure in each component. It was originally proposed in 1958 to model phase separation in binary alloys (Cahn & Hilliard, 1958; Cahn, 1959). Since then it has been used to describe various phenomena, such as spinodal decomposition (Maraldi et al., 2012), diblock copolymer (Choksi et al., 2009), image inpainting, tumor growth simulation (Hilhorst et al., 2015) or multiphase fluid flows (Badalassi et al., 2003).

There are two main approaches to describing phase transition phenomena: sharp-interface models and phase-field models. Sharp-interface models involve the resolution of a moving boundary problem, meaning that partial differential equations have to be solved for each phase. This can lead to physical (Anderson et al., 1998) and computational complications (missing reference), such as jump discontinuities across the interface. Phase-field models replace sharp-interfaces by thin transitions regions where the interfacial forces are smoothly distributed (diffuse interfaces). For this reason, phase-field models are also referred to as \emph{diffuse interface} models, and they are emerging as a promising tool to treat problems with interfaces.

From the mathematical point of view, the Cahn-Hilliard equation is a stiff, fourth-order, nonlinear parabolic partial differential equation. The elementary form of the Cahn-Hilliard equation is given by

\begin{equation} \label{element} \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t}=\nabla \cdot \left(m\left(\phi\right) \nabla \left(W’\left(\phi\right) -\epsilon ^2 \Delta \phi \right) \right) \end{equation}

where $\phi\left(\mathbf{x},t\right) \in [-1,1]$ represents the phase-field variable, which describes the location of different components (e.g., \(\phi=-1\) in oil and \(\phi=1\) in water), \(m\left(\phi\right)\) is the mobility, \(W\left(\phi\right)\) is the so-called double-well potential, and \(\epsilon\) is a length scale related to the thickness of the diffuse interface.

Two different approaches have been used to solve the Cahn-Hilliard equation: solving the original form given by Eqn.\eqref{element}, which involves fourth-order operators, or by splitting it into two second order partial differential equations by introducing an auxiliary variable — the chemical potential \(\mu\). The split version of the equation is given by

\begin{equation} \label{split1} \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t}=\nabla \cdot \left(m\left(\phi\right) \nabla \mu \right) \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \label{chempot} \mu=W’\left(\phi \right) - \epsilon^2 \Delta \phi. \end{equation}

The splitting strategy was proposed by Elliot (Elliott et al., 1989) to avoid constraints related to the continuity of the basis functions when using the finite element method with a primal formulation. It also facilitates the imposition of the boundary conditions on a circular geometry, which is the case we are interested in. Unfortunately, this comes at a price of an additional degree of freedom introduced into the solver. Nevertheless, this reformulation reduces the complexity of the problem from the numerical point of view (see (van der Zee et al., 2011)).

The spatial discretization of the governing equations is performed using isogeometric analysis (IGA). IGA is a generalization of the finite-element method that uses non-uniform rational B-splines (NURBS) to define the discrete spaces. A significant advantage of IGA with respect to finite element analysis is that the basis functions can be constructed with controllable continuity across the element boundaries, even on mapped geometries. The higher-order global continuity of the basis functions has been shown to produce higher accuracy than classical \(\mathcal{C}^0\)-continuous finite elements for the same number of degrees of freedom; and has been widely used to solve partial differential equations with high-order spatial derivatives (Gomez et al., 2008; Gomez et al., 2010; Gomez & Nogueira, 2012). Here, we will use \(\mathcal{C}^1\)-continuous quadratic splines for \(\phi\) and \(\mu\).

Strong form

The strong form of the problem is formulated as follows: find \(\phi:\Omega \times \left[0,T\right]\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) and \(\mu:\Omega \times \left[0,T\right]\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) (being \(\mu\) an auxiliary variable) such that:

\begin{equation}

\label{st1}

\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t}=\nabla \cdot \left(m\left(\phi\right) \nabla \mu\right) \quad \text{in} \ \Omega \times \left[0,T\right],

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mu=W’\left(\phi\right)-\epsilon^2 \Delta \phi \quad \text{in} \ \Omega \times \left[0,T\right], \label{st2}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\phi=g \quad \text{on} \ \Gamma_g \times \left[0,T\right], \label{st3}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

m\left(\phi\right)\epsilon^2\Delta\phi=q \quad \text{on} \ \Gamma_q \times \left[0,T\right], \label{st4}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\nabla\left(m\left(\phi\right)\mu\right)\cdot \mathbf{n}=s \quad \text{on} \ \Gamma_s \times \left[0,T\right], \label{st5}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\nabla\left(m\left(\phi\right)\phi\right)\cdot \mathbf{n}=h \quad \text{on} \ \Gamma_h \times \left[0,T\right], \label{st6}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\phi\left(\mathbf{x},0\right)=\phi_0\left(\mathbf{x}\right) \quad \text{in} \ \Omega. \label{st7}

\end{equation}

The double well function \(W\left(\phi\right)\) is defined such that it has two local minima, which makes possible the coexistence of the different phases. Some important examples of double well functions can be found in (Gomez & van der Zee, 2017). In this work we will take the classical quartic potential

\begin{equation} W\left(\phi\right)=\frac{1}{4}\left(1-\phi^2\right)^2, \end{equation}

which is a qualitative approximation of the logarithmic double well.

The mobility \(m\left(\phi\right)\), which can be linked with the diffusivity, controls the time scale of the problem. The most common approach is to set it as a constant, \(m\left(\phi\right)=m\). Such an approach is extensively applied in both analytical and numerical studies. We will take \(m\) constant and equal to one as recommended in (Gomez et al., 2008).

The parameter \(\epsilon\) is a positive constant that defines the length scale for the problem. According to (Gomez et al., 2008), the solution to the Cahn-Hilliard equations depends only on the dimensionless number

\begin{equation} \alpha=\frac{L_0^2}{3\epsilon^2}, \end{equation}

also referred to as sharpness parameter, where \(L_0\) is a length scale of the problem. Here, we will assume that \(L_0\) is a measure of the computational domain size. Without loss of generality, \(L_0=R_2=1.0\) will be the outer radius of the quarter of annulus. The sharpness parameter \(\alpha\) usually takes values in the range \(10^3-10^4\). We will study the evolution of the phase-field variable for different values of \(\alpha\).

Weak form

The strong form of our model defined by Eqns. \eqref{st1}–\eqref{st7} is now cast in weak form and discretized using the Galerkin approach. We will only work with free-flux boundary conditions. Thus, all boundary integrals will vanish in the weak form. Let us define the functional space \(\mathcal{V} \subset \mathcal{H}^1\), where \(\mathcal{H}^1\) is the Sobolev space of square-integrable functions with square-integrable first derivative in the domain \(\Omega\). To perform space discretization we introduce the finite-dimensional space \(\mathcal{V}^h\subset \mathcal{V}\), where \(\mathcal{V}^h ={\rm span}\left \{ N_A \right \}_{A=1,\dots,n_f}\) and \(n_f\) is the number of functions on the basis. The space of weighting functions will also be \(\mathcal{V}^h\), giving rise to a Galerkin formulation. We define discrete approximations to the problem’s solution denoted by \(\phi^h\) and \(\mu^h\). Their corresponding weighting functions are \(w_{\phi}^h\) and \(w_{\mu}^h\). Then, the variational formulation of Eqns. \eqref{st1}–\eqref{st7} over the finite-dimensional space \(\mathcal{V}^h\) can be stated as follows: find \(\phi^h\), \(\mu^h\) \(\in \mathcal{V}^h\subset \mathcal{V}\) such that \(\forall\) \(w_{\phi}^h\), \(w_{\mu}^h\) \(\in \mathcal{V}^h \subset \mathcal{V}\)

\begin{equation} \int_{\Omega}w_{\phi}^h\frac{\partial\phi}{\partial t}d\Omega +\int_{\Omega}m\nabla w_{\phi}^h \cdot \nabla \mu^h d\Omega =0, \label{wf1} \end{equation} \begin{equation} \int_{\Omega}w_{\mu}^h \mu^h d\Omega - \int_{\Omega}w_{\mu}^h \phi^h \left( \left(\phi^h \right)^2-1 \right)d\Omega- \int_{\Omega} \epsilon^2 \nabla \phi^h \cdot \nabla w_{\mu}^h d\Omega= 0. \end{equation}

The solutions \(\phi^h\) and \(\mu^h\) are defined as \begin{equation} \phi^h(\mathbf{x},t)=\sum_{A=1}^{n_f}\phi_A\left ( t \right )N_A\left ( \mathbf{x} \right ), \end{equation} \begin{equation} \mu^h(\mathbf{x},t)=\sum_{A=1}^{n_f}\mu_A\left ( t \right )N_A\left ( \mathbf{x} \right ). \end{equation}

Results

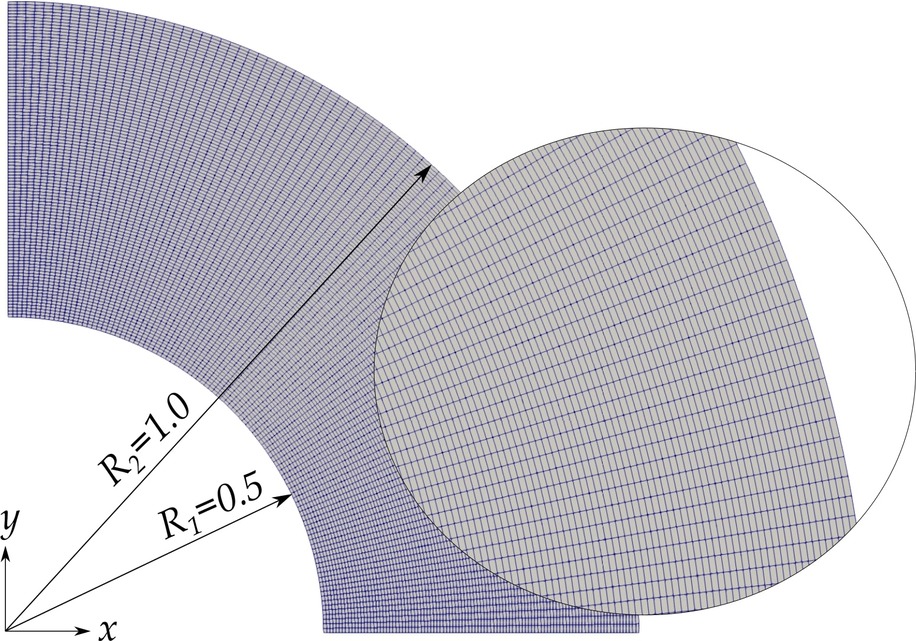

We consider the split form of the Cahn-Hilliard equation on an open quarter-annulus domain \begin{equation} \Omega = { (x,y) \in \mathbb{R}^2 : x > 0, y > 0, R_1^2 < x^2 + y^2 < R_2^2 }, \end{equation} with inner radius \(R_1=0.5\) and outer radius \(R_2=1\). We employ a computational mesh comprised of \(128^2\) \(\mathcal{C}^1\)-quadratic elements; see the figure below.

The usual setup for numerical simulations of the Cahn-Hilliard equation is as follows: a randomly perturbed homogeneous solution is allowed to evolve in a sufficiently large computational domain with periodic boundary conditions. Periodic boundary conditions would make no sense in our case, since we are not considering a square domain. Instead, we prescribe free-flux boundary conditions on the entire domain for \(\phi\) and \(\mu\). The initial condition is given by \begin{equation} \phi_0\left(\mathbf{x}\right)=\bar{\phi}+r, \end{equation} where \(\bar{\phi}\) is a constant (referred to as the volume fraction) and \(r\) is a random variable with uniform distribution in \([-0.05,0.05]\).

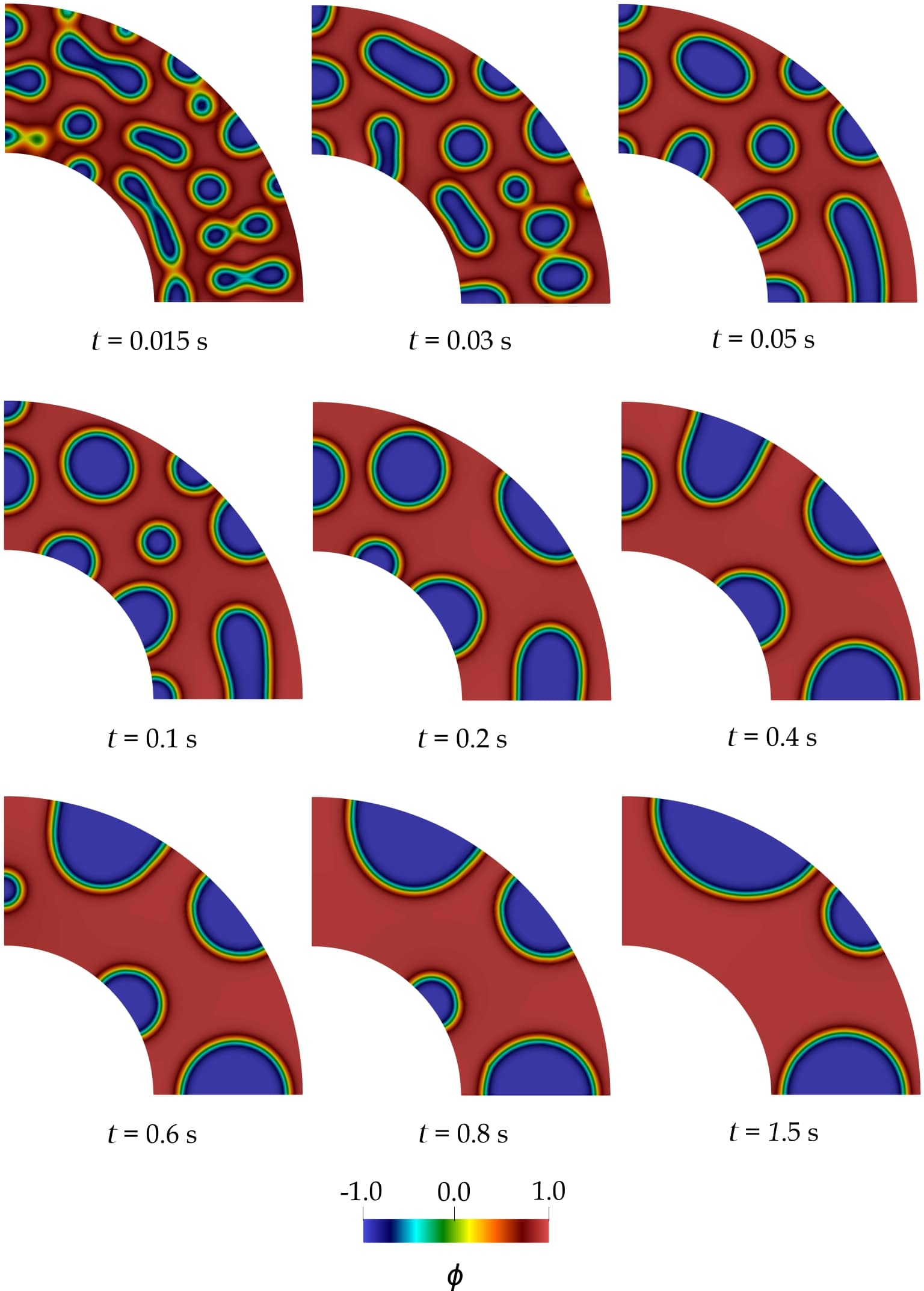

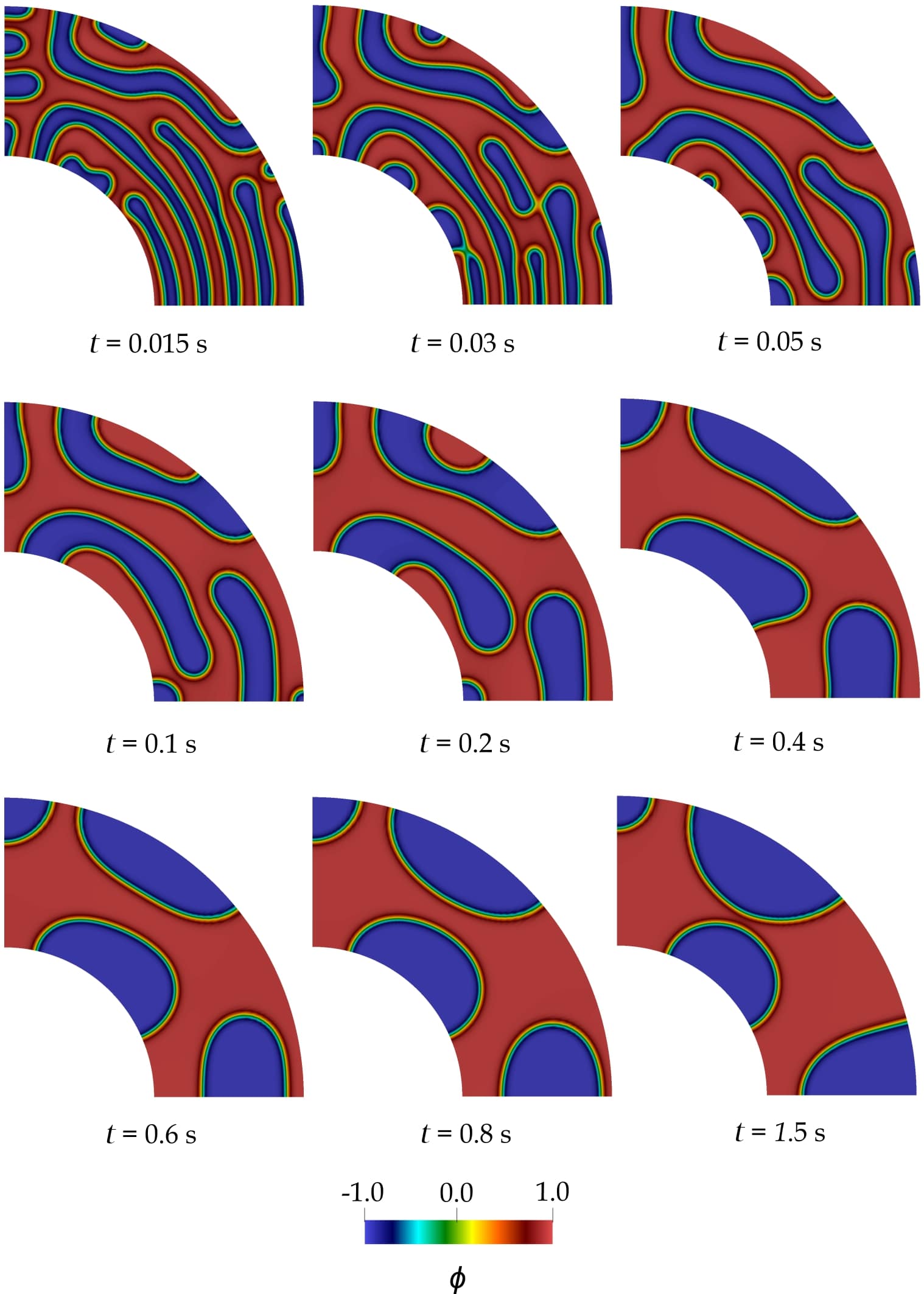

With this numerical setup we present two test cases which are defined by the sharpness parameter \(\alpha\) and the volume fraction \(\bar{\phi}\). We take \(\alpha=1500\), \(\bar{\phi}=0.3\) for the first case, and \(\alpha=3000\), \(\bar{\phi}=0.1\) for the second case.

The left figure below shows snapshots of the solution at different times for \(\alpha=1500\) and \(\bar{\phi}=0.3\). We observe two main processes that take place at very different time scales: phase separation and coarsening. The Cahn-Hilliard equation is unstable under random perturbations within the spinodal region, and, thus, two phases will develop. Phase separation takes place at \(t\approx 0.01\) s. The concentration is driven to the binodal points in a very fast process. After the phase separation, the coarsening process starts. During the coarsening process, bubbles merge with each other to reduce the surface energy, acquiring a circular shape. This process finishes when there are only two regions occupied by the two components of the mixture and they achieve the equilibrium topology. This is occurs at the steady state (data not shown).

Note: Spinodal decomposition occurs when one thermodynamic phase spontaneusly (i.e., without nucleation) separates into two phases. The spinodal region is the region of the phase diagram where this occurs.

The right figure below shows snapshots of the solution at different times for \(\alpha=1500\) and \(\bar{\phi}=0.3\). This test case is more challenging than the previous one, since the parameter \(\alpha\) is larger, and, thus, the interfaces are thinner. The parameter \(\alpha\) not only affects the thickness of the interface but also modifies the time scale of the problem. The separation process is faster for \(\alpha=3000\) than for \(\alpha=1500\). Phase separation in this case takes place at the beginning of the simulation. On the other hand, the coarsening process is slower. The bubbles start acquiring the equilibrium topology, that is, a circular shape, later in time compared to the previous example. The initial volume fraction \(\bar{\phi}\) plays an important role in the topology of the solution. The topology of the solution for \(\bar{\phi}=0.1\) shows a more connected pattern than that of the solution for \(\bar{\phi}=0.3\). In contrast to the case defined by \(\bar{\phi}=0.3\), for \(\bar{\phi}=0.1\) there is no nucleation, and the coarsening process is more continuous over the simulation.

Conclusions

We presented a numerical methodology to solve the Cahn-Hilliard equation on a quarter-annulus domain. Our computational method is based on isogeometric analysis, which allows us to generate the \(\mathcal{C}^1\)-continuous functions required to solve this equation in a variational framework. We adopt the split form of the equation to reduce its order, and facilitate the imposition of the boundary conditions on the circular geometry. Time discretazion is performed using the generalized \(\alpha\)-methods, which provides second order accuracy and \(A\)-stability. We analyzed the solution over time for different values of \(\alpha\) and \(\bar{\phi}\). The parameter \(\alpha\) affects the thickness of the interface and the time scale of the problem. As we increased \(\alpha\), the separation process was faster, and the thickness of the interface became thinner. The initial volume fraction \(\bar{\phi}\) modifies the topology of the solution. Smaller values of \(\bar{\phi}\) produce more continuous patterns without nucleation.

References

-

The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1958

-

-

International Journal of Engineering Science, 2012

-

SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics, 2009

-

Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences, 2015

-

-

-

-

Numerical Methods for Partial Differential Equations, 2011

-

Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2008

-

Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2010

-

Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2012Higher Order Finite Element and Isogeometric Methods