Phase-field Modeling of Dendritic Solidification

Phase-field equation for solidification processes

Liquid-solid phase transformations usually refer to solidification and melting. The formation of complex microstructures during the solidification from a liquid phase, such as formation of snow flakes or metallic alloys, and the accompanying diffusion and convection processes in the liquid and solid have been widely studied in the literature (Boettinger et al., 2002; Flemings, 1974; Kühn et al., 1986). In particular, the evolution of microstructural scale of dendrites during the solidification process determines many physical and mechanical properties of metals, since almost every metallic system originates from the liquid state. \(\phi \in [-1,1]\)

A phase-field formulation that describes the solidification process is as follows: \begin{equation} \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t} = \Delta \phi - \frac{W’(\phi)}{\epsilon^2} + \frac{\rho H}{\sqrt{2\sigma}} \frac{\theta - \theta_m}{\theta_m} G’(\phi) \label{1} \end{equation} \begin{equation} \rho C_v \frac{\partial \theta}{\partial t} + L \phi’ \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (k(\phi) \nabla \theta) \label{2} \end{equation}

where \(\phi \in [-1,1]\) represents the phase-field variable, which describes the location of different components (e.g., \(\phi = -1\) in the solid and \(\phi = 1\) in the liquid), \(\theta\) is the temperature, \(\theta_m\) is the melting temperature, \(H\) represents the interfacial enthalpy per unit mass, \(\omega\) is the kinetic undercooling coefficient, \(C_v\) is the heat capacity per unit mass, \(\rho\) is the density, \(l\) is specific latent heat (energy per unit mass), \(k\) is the thermal conductivity, \(\sigma\) is the surface tension and \(h\) is an interpolatory function that verifies \(h(+1) = 1, h(-1) = 0\), e.g., \(h = \frac{1}{2} (1 + \phi)\). The thermal conductivity is considered to be a function of the phase-field to account for different conductivity in the solid and liquid phases. We take \(k(\phi) = (1 + \phi) k_s + (1 - \phi) k_l\), which satisfies that \(k(+1) = k_s\), \(k(-1) = k_l\). The function \(W(\phi)\), also referred to as the double-well potential, is defined such that it has two local minima, which makes possible the coexistence of the different phases. Some important examples of double well functions can be found in (Gomez & van der Zee, 2017). In this work we will take the classical quartic potential \(W(\phi) = \frac{1}{4} (1 - \phi^2)^2\). The function \(G(\phi)\) vanishes in the pure phases. Depending on the form of the functional \(G(\phi)\), the phase-field will converge faster or slower to the generalized Stefan problem. Here we will use the expression \(G(\phi) = (1 - \phi^2)^2\). One key aspect to achieve good agreement with the reality of interest behind dendritic solidification is surface tension anisotropy. Herein, we introduce anisotropy by assuming that \(\sigma\) depends on the unit normal to the liquid-solid interface, this is,

\begin{equation} \sigma = \sigma_0(1 + \delta \cos(\alpha - \alpha_0)), \end{equation}

where \(\bar{\sigma}\) is the mean value of \(\sigma\), \(\delta\) is the strenght of the anisotropy, \(q\) is the mode number of anisotropy, and \(\alpha\) is the initial offset angle. The angle of the normal to the surface, \(\alpha\), is defined from the phase-field as

\begin{equation} \alpha = \arctan\left(\frac{\partial \phi / \partial y}{\partial \phi/ \partial x}\right). \end{equation}

Weak form

The strong form of our model defined by Eqs. \eqref{1} and Eqn.\eqref{2} is now cast in weak form and discretized using the Galerkin approach. Let us define the functional space \(V \subset H^1\), where \(H^1\) is the Sobolev space of square-integrable functions with square-integrable first derivative in the domain \(\Omega\). To perform space discretization we introduce the finite-dimensional space \(V_h \subset V\), where \(V_h = \text{span} \{ N_A \}_{A=1}^{n_f}\), and \(n_f\) is the number of functions on the basis. The space of weighting functions will also be \(V_h\), giving rise to a Galerkin formulation. We define discrete approximations to the problem’s solution denoted by \(\phi^h\) and \(\theta^h\). Their corresponding weighting functions are \(w_{\phi}^h\) and \(w_{\theta}^h\). Then, the variational formulation of Eqs. \eqref{1} and Eqn.\eqref{2} over the finite-dimensional space \(V_h\) can be stated as follows: find \(U_h = \{\phi^h, \theta^h\} \in V_h \subset V\)

such that \(\forall W_h = \{w_{\phi}^h, w_{\theta}^h\} \in V_h \subset V\), \begin{equation} \int_{\Omega} w_{\phi}^h \frac{\partial \phi^h}{\partial t} \, d\Omega + \int_{\Omega} w_{\phi}^h \frac{W’(\phi^h)}{\epsilon^2} \, d\Omega + \int_{\Omega} \nabla w_{\phi}^h \cdot \nabla \phi^h \, d\Omega + \int_{\Omega} w_{\phi}^h \frac{\rho H}{\sqrt{2 \sigma}} \left( \frac{G’(\phi^h) (\theta^h - \theta_m)}{\theta_m} \right) \, d\Omega =0, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \int_{\Omega} w_{\theta}^h \rho C_v \frac{\partial \theta^h}{\partial t} \, d\Omega - \int_{\Omega} w_{\theta}^h L \phi’(\phi^h) \frac{\partial \phi^h}{\partial t} \, d\Omega + \int_{\Omega} \nabla w_{\theta}^h \cdot k(\phi^h) \nabla \theta^h \, d\Omega=0. \end{equation}

The solutions \(\phi^h\) and \(\theta^h\) are defined as \begin{equation} \phi^h(x,t) = \sum_{A=1}^{n_f} \phi_A(t) N_A(x), \end{equation} \begin{equation} \theta^h(x,t) = \sum_{A=1}^{n_f} \theta_A(t) N_A(x). \end{equation}

Results

Our computational domain is the square \(\Omega= \left[0,0.1 \right] \times \left[0,0.1 \right]\), where the units are in cm. We employ a computational mesh comprised of $512^2$ \(\mathcal{C}^1\)-quadratic elements. We impose periodic boundary conditions for \(\phi\) and \(\theta\). We choose a suitable time step of \(\Delta t = 10e-6\) s to ensure good numerical stability, specially at the beginning of the simulation. As an initial condition, we set a square-shaped seed located at the center of the domain. The reason for using a square-shaped crystal, instead of one with a smoother shape like a circle, is because the corners of the square will accelerate the formation of dendritic structures. The temperatures inside and outside the seed are 1700 K and 1500 K, respectively. The parameters used in all the simulations are summarized in (Gomez et al., 2019). These parameters correspond to an Nickel-Copper alloy. In the following simulations, we will show the relations between the anisotropy modes and the shapes of crystals.

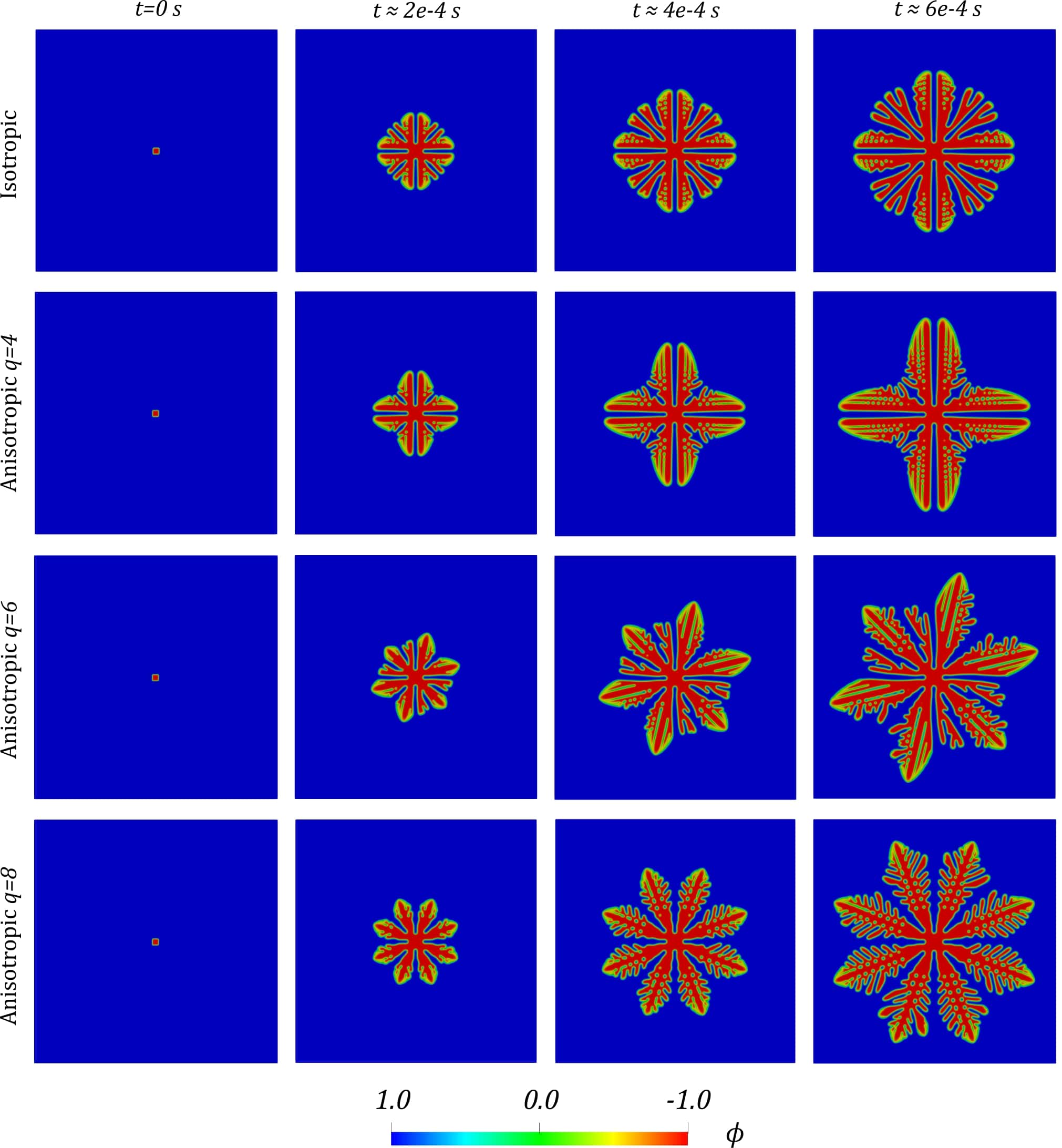

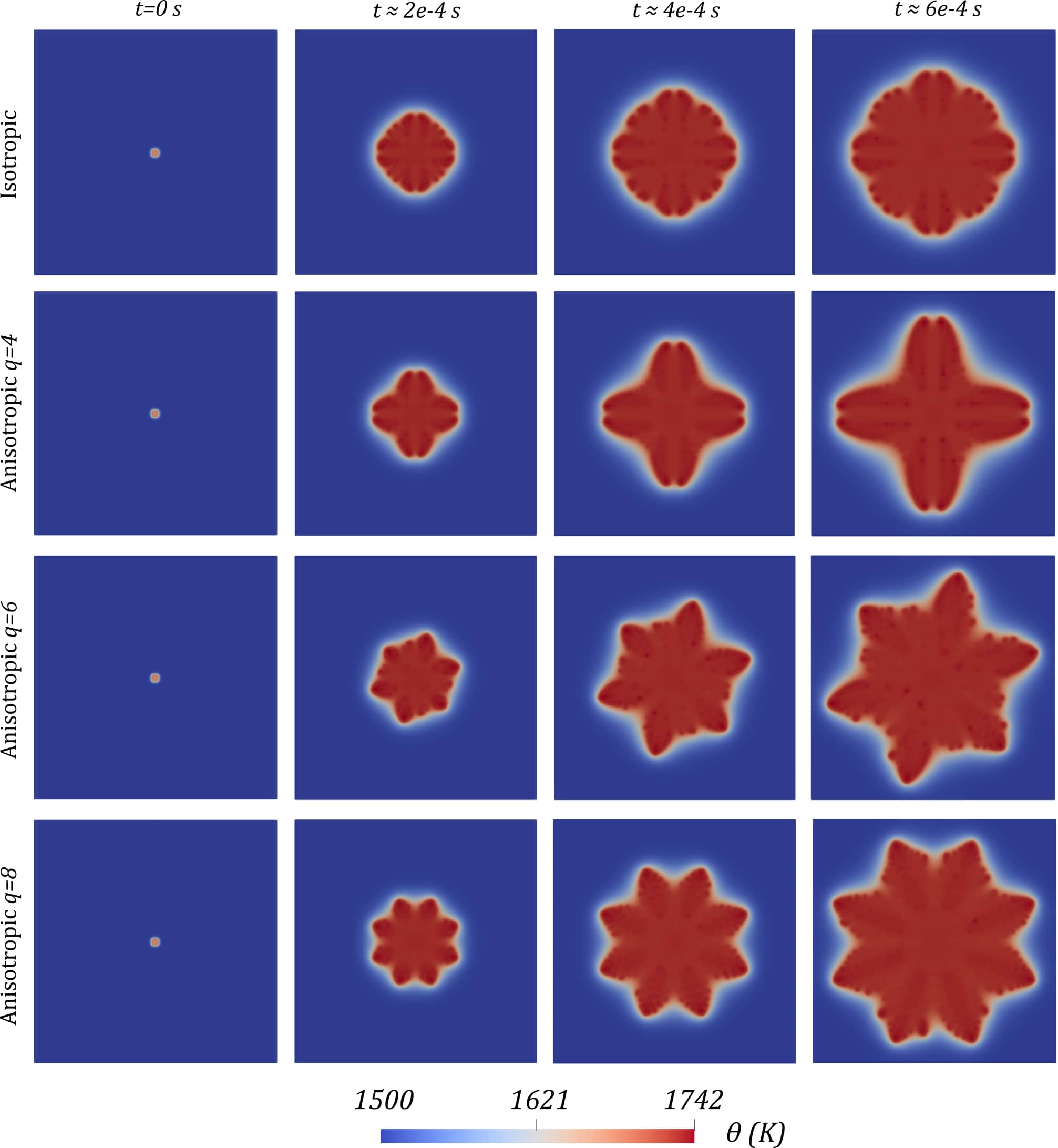

The Figures below show the evolution of the phase-field variable and the temperature field over time for different values of \(q\). For all simulations nucleation starts at the center of the domain, and it triggers the solidification process. The phase change is achieved by undercooling the liquid phase below its melting temperature.

In the first computation, perfect isotropic growth is considered, i.e. \(\sigma=\bar{\sigma}\) throughout the entire simulation. For this case we obtain symmetric dendritic patterns similar to those formed during viscous fingering. Tip splitting is observed as the crystal grows, producing new branches with tips that mantain a circular shape. For the anisotropic case with \(q = 4\), we see features of both the isotropic case and the dendritic structure. The dendritic structure is present in the formation of the principal branches, which are four in this case due to the anisotropy mode chosen. The isotropic features are observed in the viscous finger-like structures that emanate from the principal branches. The overall look of the pattern is symmetric, even though we are considering surface tension anisotropy. When we increase the anisotropy mode number to \(q = 6\), we get a completely asymmetric pattern. We can observe six main branches and four secondary branches. For \(q = 8\) we get the typical snowflake-like pattern with a non-symmetric side branching. In general, dendrites whose preferred direction is inclined with respect to the thermal gradient grow faster in order to maintain their relative tip positions during the splitting. These tips of the inclined dendrites lie slightly behind those of well aligned dendrites. We can say that there is a growth competition among the different dendrites, which results in a natural selection of the grains that grow with a smaller angle with respect to the temperature

Conclusions

We presented a numerical methodology to solve a phase-field model of dendritic solidification with surface tension anisotropy on a two-dimensional domain. Our computational method is based on isogeometric analysis, which allows us to generate the \(\mathcal{C}^1\)-continuous functions required to solve this equation in a variational framework. Time discretazion is performed using the generalized \(\alpha\)-method, which provides second order accuracy and \(A\)-stability. We analyzed the evolution of the phase-field variable and the temperature field over time for different anisotropy mode numbers. Our results show that symmetric dendritic finger patterns can form in the presence of anisotropy.

References

-

-

-

-

-

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 2019